Designing a sustainable veterinary landscape

Multidisciplinary collaboration involving vets and landscape architects can help to integrate ‘One Health’ principles in to the fabric of a veterinary practice site.

Catherine Higham BA(Hons) MA CMLI and Laura Higham BVM&S MSc MRCVS

This article was originally published in the May 2021 edition of The Veterinary Edge magazine. Read the original article here.

There is a growing awareness of sustainability issues in veterinary activities, pet ownership and farm animal production. Members of the veterinary professions are uniquely placed to address a number of sustainability challenges through the animals under their care. However, veterinary organisations can also consider creating more sustainable working environments by rethinking the layout and function of external spaces within veterinary practice sites, with an aim to improve the wellbeing of animals, people and the natural environment. Whether situated in rural, semi-rural or urban settings, there is significant scope to apply both small, step-wise changes, as well as more radical transformations to the UK’s 5,705 veterinary practice sites (RCVS, 2017) in order to put ‘One Health’ principles in to practice.

In this article, we provide an overview of the role of landscape architects in enhancing our natural and built environments. We demonstrate how multidisciplinary collaboration, in this example involving vets and landscape architects, can help to integrate ‘One Health’ principles in to the fabric of a veterinary practice site, using a case study and example designs for a veterinary practice scheme in the Cotswolds, UK.

Photo credit: Rachel Duncan

Landscape Architecture

Landscape architects plan, design and manage the outdoor environment (both natural and built) for the benefit of the public, at a range of scales from small parks and gardens, schools and hospitals, to industrial, commercial and city centre developments and regional planning-scale projects. We have to think beyond our own lifespan, creating long-term environmentally and socially sustainable spaces for future generations to live, work and enjoy. Ecology and habitat creation and restoration, burial sites, residential developments, woodland or water management (e.g. flood mitigation) projects and historic landscapes, are a few examples of projects which involve, and are often led by landscape architects.

Time is a fundamental element of landscape architecture. The designer’s involvement is momentary in the evolution of a landscape, and at its best, is a subtle intervention that leaves no trace of the designer’s hand. A landscape architect may simply initiate a natural process - for example, the planting of a woodland or diversion of a watercourse, or make sensitive adjustments to a space to enable new social activities or functions. Vegetation, topography, water, structures and other material elements, as well as how a landscape is used, will evolve and develop over time.

“There is never a fixed end product of landscape design, merely a point in time, when a place wears a particular form.” (Dee, 2012)

The way in which a landscape functions and is experienced is also determined by the season, weather, and time of day (or night) – factors that must be considered in the design of a space. A deciduous woodland glade feels very different on a hot mid-summer day, compared to a drizzly autumn evening, or a bright snow-covered winter morning.

Photo credit: Rachel Duncan

The multiple benefits of trees

Trees are increasingly valued features of the urban landscape, as the most effective landscape medium for climate and flood resilience, pollution mitigation, biodiversity, as well as being of high cultural value for health and well-being, recreation and historical importance. To create positive outdoor public spaces, mature existing trees are essential for their spatial and structural qualities - defining boundaries, creating enclosure and ‘roof-scape’, and marking important thresholds; and also for shelter from the wind, and shade from the sun. Deciduous trees growing on the sunny side of a building offer natural climate control; bare branches allow for solar gain in winter, and leaves provide shade in the summer when it is needed most.

Working with, not against, the existing site

A ‘minimal intervention’ approach to design projects is often the most sustainable. This means working with the existing landscape by retaining and enhancing what is already there; for example, preserving existing trees and vegetation where possible, reusing on-site materials and reducing the need to import or dispose of large amounts of earth when landform alteration is required. Planting design and materials selection is often informed by the existing local landscape ‘palette’.

Landscape design of a veterinary site for One Health benefits

One Health is the concept that human health and animal health are interdependent and bound to the health of the ecosystems in which they exist (OIE, 2020). Vet Sustain has further interpreted the One Health concept in its six ‘veterinary sustainability goals’, aligned with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, seeking to highlight the roles of veterinary professionals in driving sustainability, and to unite the professions around the goals and tangible actions required to address multiple challenges facing our society (Vet Sustain, 2020).

Veterinary practices and businesses are increasingly adopting policies and practices in a transition towards more sustainable operations, by devising their own sustainability policies, recruiting designated specialists or seeking accreditation. Practices that are starting to consider how they can, on a practical level, adapt their places of work to accommodate the health and wellbeing of the environment, wildlife, staff, clients and their animal patients may wish to consider implementing a number of the small-scale interventions suggested in Box 1.

Box 1: Examples of small-scale interventions for promoting One Health in the external environment of a veterinary practice

- Insect stacks/hotels

- Bird and bat boxes

- Hedgehog ‘highways’ (gaps below any fences to allow easy movement of small mammals)

- Compost bin for staff food waste

- Water butt - harvesting rainwater for watering plants or washing down dirty areas

- Sustainable urban drainage systems

- Recycling and Terracycle stations for the community, including for pet food packaging

- Bike racks for staff to encourage cycling

- Planters with wildflowers, vegetables or herbs

- New tree planting, wherever there is space

- Wild untamed areas to encourage a range of wildlife species

- External seating for staff and clients (more important now, in a post-Covid-19 world), near to the garden/green space

Practices may alternatively consider a more comprehensive redesign of their external space embedding the One Health principles, as discussed in the following section.

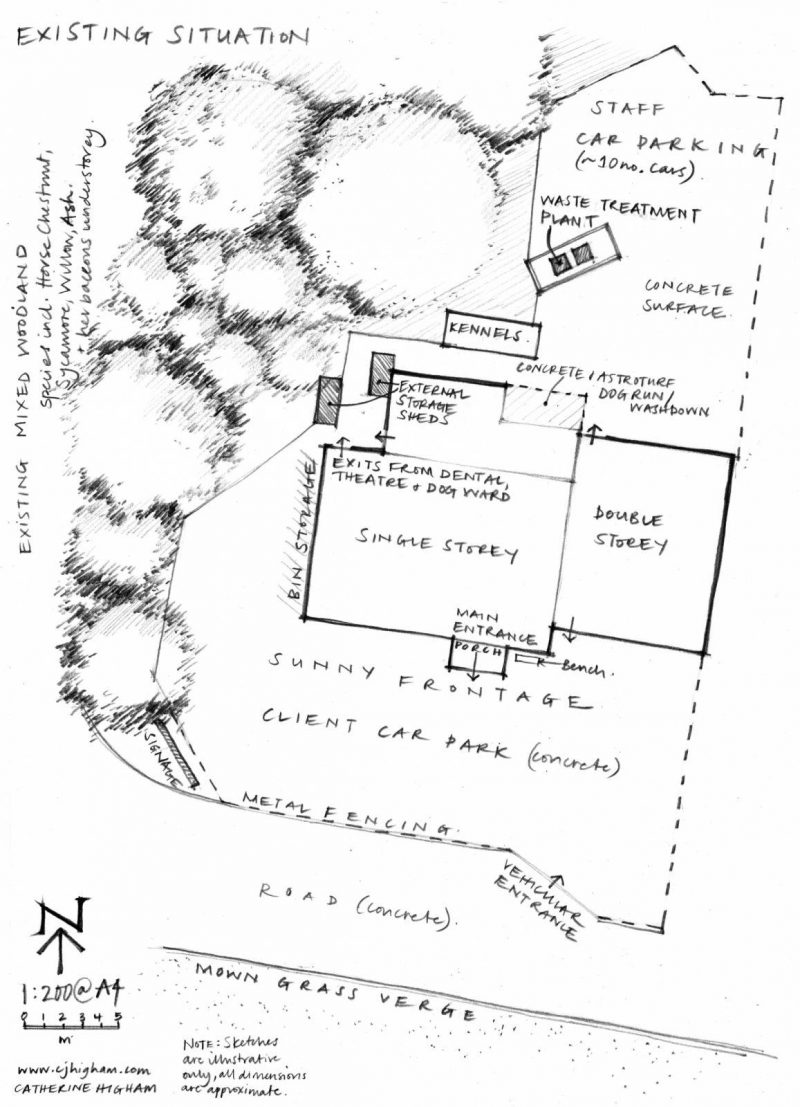

Figure 1: Sketch of Cotswold Vets existing site. Copyright Catherine Higham 2020.

Case study: A UK practice

The project used as a case-study for the purpose of this article is a family-run, independent companion animal practice in the Cotswolds, UK. The existing site (see Figure 1) has been built and purposed relatively recently, with a concrete car park as the main outdoor space. Applying the previously described principles, landscape proposals could look beyond the site boundary for design prompts; for example, the band of woodland immediately north of the building, the nearby network of lakes and wetlands, and the agricultural character of the surrounding landscape, including tree belts and hedgerows.

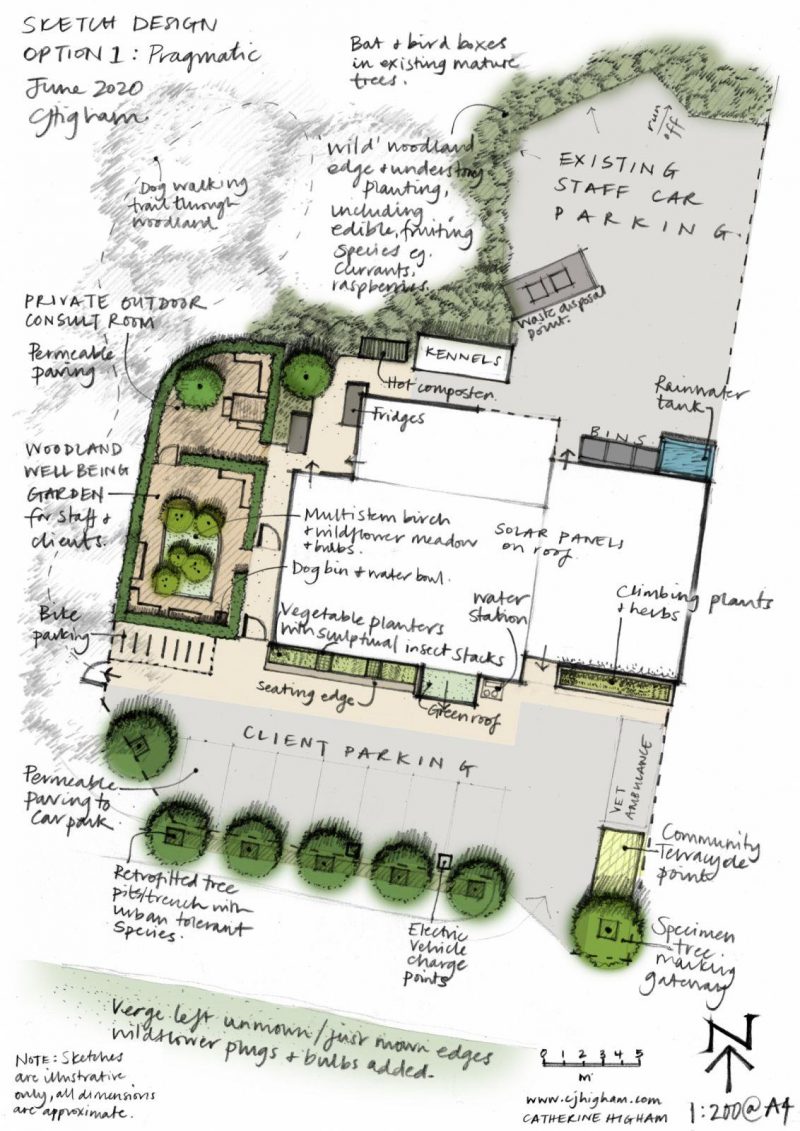

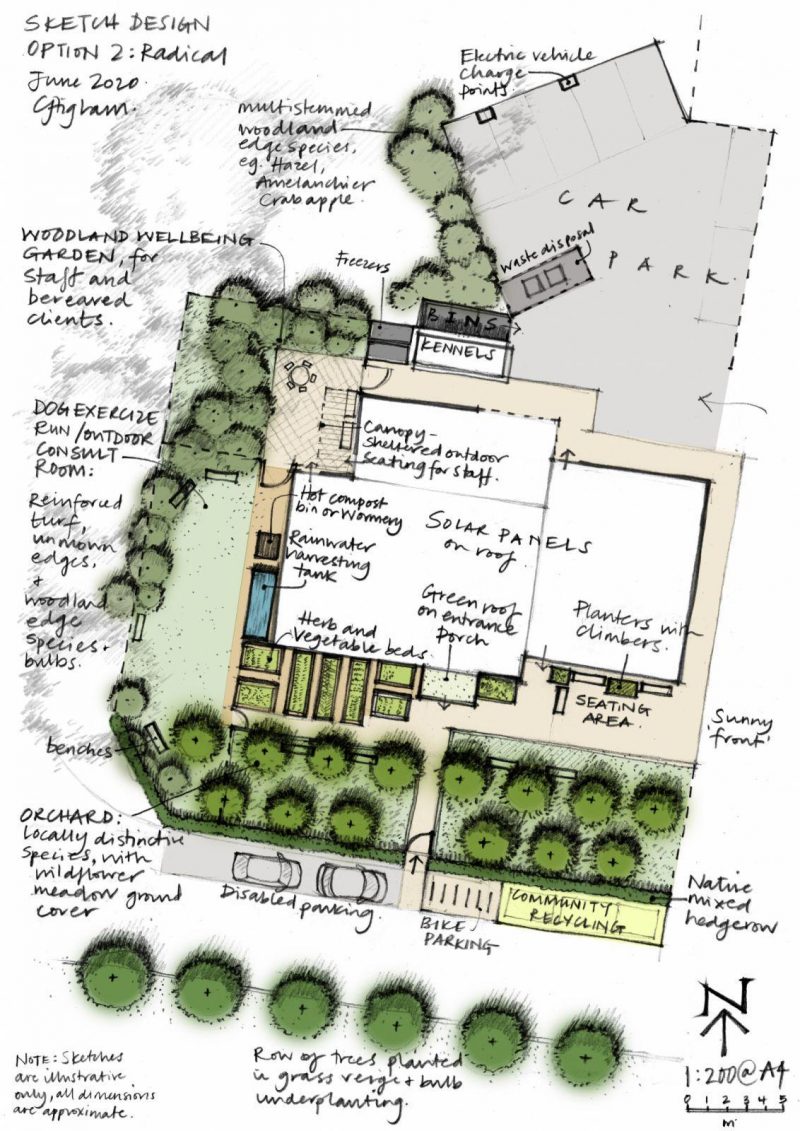

The designs in Figures 2 and 3 illustrate two possible schemes for the site, incorporating landscape elements arranged to create a more sustainable external environment. Figure 2 represents a lower intervention, more pragmatic proposal; Figure 3 presents a more radical and idealistic scheme. In both designs, designated areas are created to encourage greater use of the practice’s outdoor space, with the aims of:

- Enhancing staff wellbeing and encouraging sustainable lifestyles;

- Increasing local biodiversity and establishing wildlife corridors (if connected with neighbouring green-spaces);

- Supporting patient (and staff pet) welfare and management;

- Providing distressed and bereaved clients with quiet green places to sit; and

- Promoting community sustainability projects by inspiring clients, and leading by example.

Figure 2: Sketch design option 1: Pragmatic. Copyright Catherine Higham 2020.

Figure 3: Sketch design option 2: Radical. Copyright Catherine Higham 2020.

In practice

A number of practices have succeeded in integrating landscape features in to their premises to bring sustainability benefits. Chris Copeman, owner of the UK’s first Passivhaus veterinary clinic Bryn Veterinary Centre in Wigan, installed a sustainable urban drainage system (SUDS) draining in to a bed of dog wood, to reduce water bills, mitigate flooding and reduce water pollution. PDSA Kirkdale have created a wildlife area, planting 20 native whips and building a raised bed to populate with pollinator-friendly species that could be fed to hospitalised rabbits – cornflowers, nasturtiums and thyme, for example – providing both environmental and animal welfare benefits. The staff also benefit from the nearby seating area during their breaks (Wensley, 2020).

Rachel and Hamish Duncan, owners of 387 Veterinary Centre in Great Wyrley, introduced more than 100 bee-friendly lavender plugs in to their gravel borders around the car park and front of the premises, and gave free packets of bee-friendly wild flower seed to clients. They have also planted several fruit trees to attract bees during the blossom season, and have installed a bench in the garden allowing team members to enjoy some peaceful outdoor time at lunchtime (Kernot, 2007). The British Bee Veterinary Association run a national programme encouraging veterinary practices to plant a 1m2 plot with flowering plants that will attract pollinating bees, and offer free Bee-Friendly Practice packs (BBVA, 2020). Ballymena Pet Vets run by Mary Davey is a ‘bee friendly practice’, installing wildflower planters in their outdoor yard. They have also volunteered as a drop-off point for Terracycle.

A Sustainable Urban Drainage System (SUDS) at a veterinary practice. Photo credit: Chris Copeman.

Photo credit: Rachel Duncan

Conclusions

There are a number of constraints to the design and maintenance of veterinary premises, for example the need to maximise parking, time required to maintain green spaces and limited financial resources for landscape architects and construction works especially during these challenging times. However, there are a number of small features that can be added to a site that can bring multiple benefits to the team, clients, patients and the environment. Taking this further, redesigning veterinary sites can bring more significant and lasting benefits, whilst showcasing veterinary professionals as practitioners of One Health, championing the wellbeing of all walks of life and our natural environment in our day-to-day work.

Catherine Higham is a landscape architect and artist based in Sheffield, specialising in site-specific and experimental approaches to landscape architecture, often involving trees: [email protected]

Laura Higham is a veterinary consultant and director of Vet Sustain, the organisation championing sustainability in the veterinary professions: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Ben and Anna Gamsa of Cotswold Vets for agreeing to share their plans and agreeing to feature in this article. Thank you also to Chris Copeman, PDSA Kirkdale, Rachel and Hamish Duncan and Mary Davey for offering examples of landscaping work at their veterinary practices and photographs for this article.

References

British Bee Veterinary Association (BBVA) (2020) How to get involved [online] Available from: https://britishbeevets.com/how-to-get-involved/ [Accessed 11 Nov 2020].

Dee, C. (2012) To Design Landscape: Art Nature and Utility. 1st Ed. Routledge, Abingdon UK.

Kernot, H. (2017) Bee-friendly practice scheme: great for bees, clients and staff. Vet Times. Available from: https://www.vettimes.co.uk/news/bee-friendly-practice-scheme-great-for-bees-clients-and-staff/ [Accessed 11 Nov 2020]

Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) (2017) RCVS Facts [online] Available from: https://www.rcvs.org.uk/news-and-views/publications/rcvs-facts-2017/ [Accessed 7 July 2020]

OIE (2020) One Health “at a glance”. World Organisation for Animal Health, Paris. [online] Available from: https://www.oie.int/en/for-the-media/onehealth/ [Accessed 11 August 2020].

Vet Sustain (2020) The Veterinary Sustainability Goals. [online] Available from: https://vetsustain.org/assets/downloads/VetSustain-VeterinarySustainabilityGoals.pdf [Accessed 11 August 2020].

Wensley, S. (2020) Restoring nature through veterinary practices. Veterinary Practice Magazine. Available from: https://veterinary-practice.com/article/restoring-nature-through-veterinary-practices [Accessed 11 Nov 2020].