Is it possible to measure whether an animal has a good life?

As vets, our guiding purpose is to ensure the health and welfare of the animals under our care. But how do we, as humans, know whether an animal has a good life?

Rebekah Sullivan

As vets, our guiding purpose is to ensure the health and welfare of the animals under our care. Our aim must surely be to strive for the highest possible welfare standards such that an animal has a good life. But how do we, as humans, know whether an animal has a good life? Can we measure welfare and subsequently measure the impact of any interventions made in an attempt to improve welfare? And, can this deliverance of a good life be done sustainably?

Those of us who graduated aeons ago were probably taught the principles of The Five Freedoms (FAWC, 1979, Webster 2016) such that we understand all the things that an animal should be free from in order to avoid poor welfare. More recently, welfare science has shifted focus such that it is no longer enough to avoid poor welfare but steps should be taken to proactively provide the basis for positive welfare and a good life. The Five Domains model utilises this approach, considering the state of an animal through the four functional domains of nutrition, environment, health and behaviour and the subsequent affective consequences for an animal’s mental state (Mellor and Beausoleil 2015). Practically speaking, what methods or tools exist for rapid welfare assessment that can be repeated?

This article specifically considers donkeys and mules. Teams from The Donkey Sanctuary are frequently required to assess and advise on the health and welfare of donkeys and mules in a variety of contexts, both in the UK and internationally. In developed countries donkeys may be kept as pets, companion animals for other species, used in animal-assisted therapy, assist in horticulture and agro-forestry initiatives, be found as beach donkeys or at tourist attractions. Semi-feral populations also exist.

Globally, donkeys are pivotal to the livelihoods of many families, providing a means of transportation of cargo, water and people, animal-traction and may be used as production animals.

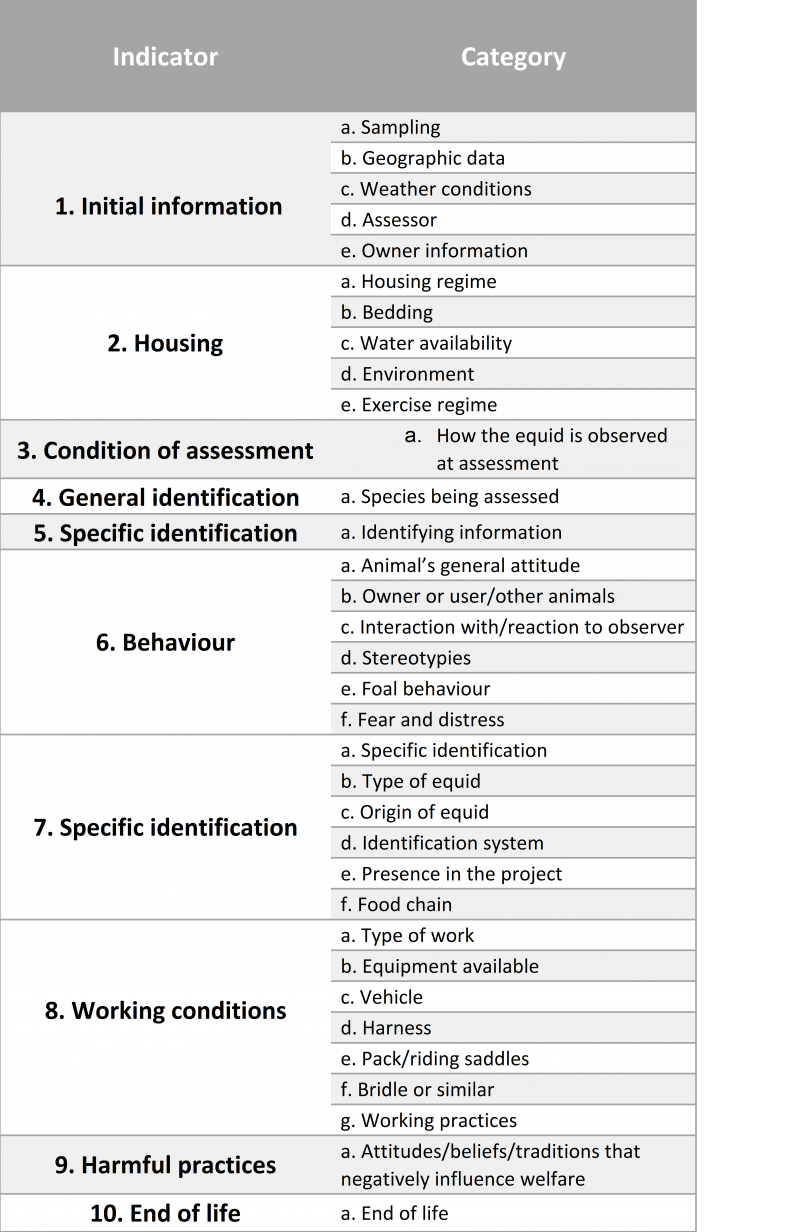

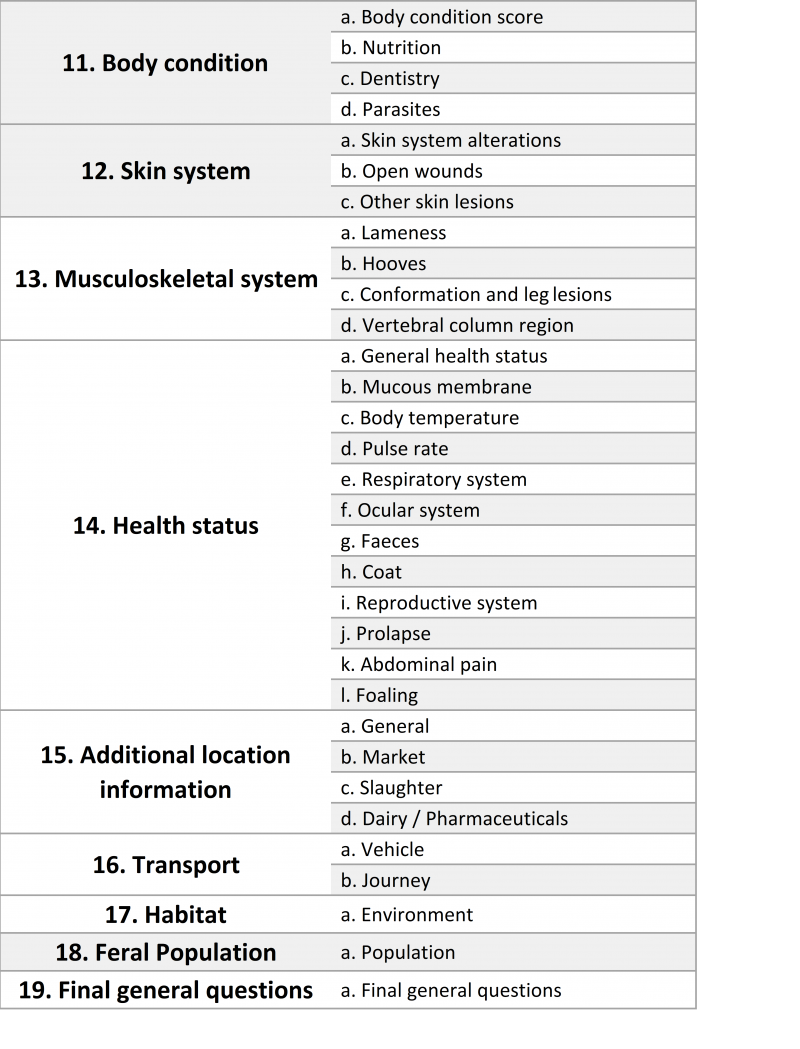

Is it possible to assess whether the donkeys, across all of these different contexts have a good life, in the same way? The Equid Assessment and Research Scoping tool (EARS) has been developed for this very purpose (Raw et al 2020). EARS is, essentially, a bank of almost 300 questions that have been subdivided into indicators, such as housing, behaviour and general health. A full list of the indicators is given at the end of this article. The questions were developed and tested over a period of 3 years, using input from vets, paraprofessionals, behaviourists, data scientists and harness experts who are experienced in working with donkeys and mules around the globe. From the question bank, bespoke protocols can be built for assessing welfare in different contexts; for example, there are production equid, feral, companion and working equid protocols. By using a standardised set of questions, welfare may be objectively and systematically recorded. Moreover, equids in the same context can be re-evaluated at a later date, using the same set of questions, allowing objective comparison between the datasets. In this way, a more complete picture of the welfare in any one situation is built up over time and the impact of an intervention can be reflected upon and refined as necessary.

This data can be used in the immediate term to appraise the welfare of individuals or groups. Over the longer term, it helps to identify common themes of negative and positive welfare such that our knowledge base expands and we can tailor what advice is most relevant in different contexts.

For example, in companion donkeys, accumulated data may indicate common themes around weight and condition score – we all know that obesity is of growing concern amongst companion animals in the UK. Being able to objectively measure whether this is actually the case would facilitate provision of accurate advice to vets and owners alike. In working equids, we might suspect that poorly manufactured and fitted harness equipment are the cause of skin lesions. However, before embarking upon a programme of education regarding good harness use, data should be obtained to investigate whether poorly fitted harness equipment is indeed being used and/or are there other variables that might contribute to skin lesions, such as housing hazards, or injurious human-animal and animal-animal interactions. Frequently there is more than one cause for a welfare issue and by having an awareness of all the factors a more holistic and sustainable intervention programme can be devised.

Sustainability has to be a key objective. Any attempt to improve welfare must be capable of being a long-term solution. Where positive welfare is identified this should be recognised as such and efforts made to disseminate information regarding how such welfare can be achieved. Sustainability can be defined and measured in terms of financial, environmental or longevity aspects of welfare changes. Currently EARS data is recorded on tablets so there is no need for lots of paperwork flying around, getting rained on or eaten by an inquisitive animal. Gone are the days of huge filing cabinets toppling over with the weight of records. Cloud-based systems can be used to store large quantities of data that are potentially accessible from locations around the globe. Virtual learning platforms can be used to host discussion groups and online training such that people can learn remotely without the need to travel. Nothing can replace the actual reality of being alongside an animal and their handler, in the community they live, assessing and discussing the welfare together, but by providing options to do some of the groundwork online, more time can then be devoted to being with the animals and people when you are there.

In summary, welfare assessment can and should be done regularly and there are several tools out there that exist for this purpose. The time devoted to focusing on welfare will reap many rewards for animals and people. Any assessment and intervention should always be done through engaging with communities – there will likely be much greater long-term success if animal owners and handlers are involved in the process, rather than being told what to do. If the advice given is evidence-based, then financially, everyone stands to benefit as money is not wasted on inappropriate projects. As welfare assessment becomes ever more commonplace, techniques for making it a sustainable process and identifying sustainable ways to improve welfare will continue to arise.

Rebekah has been a vet at The Donkey Sanctuary since 2012. Before joining the sanctuary, she worked in mixed practice in the UK and New Zealand and spent time volunteering overseas, providing care to working equids. Rebekah holds the Cert AVP (EM) and loves to provide assistance with medical cases as well as enjoying general veterinary work. Rebekah is currently seconded to the Donkey Sanctuary Operational Support team, helping to provide materials for donkey health and welfare globally and has recently started an MSc in One Health with the University of Edinburgh.

References

Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC) (1979) Farm Animal Welfare Council Press Statement. FAWC, London. [online]

Mellor .D.J. and Beausoleil .N.J. (2015) Extending the 'Five Domains' model for animal welfare assessment to incorporate positive welfare states. Animal Welfare 24 (3) pp. 241-253

Raw, Z.; Rodrigues, J.B.; Rickards, K.; Ryding, J.; Norris, S.L.; Judge, A.; Kubasiewicz, L.M.; Watson, T.L.; Little, H.; Hart, B.; Sullivan, R.; Garrett, C.; Burden, F. (2020). Equid assessment, research and scoping (EARS): The development and implementation of a new equid welfare assessment and monitoring tool. Animals, 10, 297

Webster .J. (2016). Animal Welfare, Freedoms, Dominions and ‘A Life Worth Living.’ Animals 6 (35) doi:10.3390/ani6060035